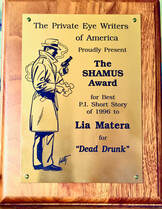

This new collection of short stories is available as an ebook on all platforms. It includes nine stories from the print collection Counsel For The Defense and Other Stories (Five Star Press, 2000) and three stories -- "The Children," "Snow Job" and Champawat (a novella) -- later published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. ********************* LOVERS AND LAWYERS TWELVE STORIES Dead Drunk Snow Job The Children Champawat The River Mouth Destroying Angel Do Not Resuscitate Dream Lawyer Performance Crime Easy Go If It Can’t Be True Counsel For The Defense Here are the opening paragraphs of the stories, in lieu of descriptions: DEAD DRUNK Winner of the Private Eye Writers of America Shamus Award for Best Short Story of 1996. First published in Guilty As Charged, ed. Scott Turow, 1996. Reprinted in The Year's Twenty-Five Finest Crime and Mystery Stories, ed. Joan Hess, 1997; The World's Finest Mystery and Crime Stories, ed. Ed Gorman, 2000; A Century of Noir, ed. Mickey Spillane and Max Allan Collins, 2002; Shamus Winners, Volume II: 1996 - 2009, ed. Robert J. Randisi, 2012. My secretary Jan asked if I’d seen the newspaper: another homeless man had frozen to death. I frowned up at her from my desk. Her tone said, And you think you’ve got problems? My secretary is a paragon. I would not have a law practice without her. I would have something resembling my apartment, which looks like a college crash pad. But I have to cut Jan a lot of slack. She’s got a big personality. Not that she actually says anything. She doesn’t have to, any more than earthquakes bother saying “shake shake.” “Froze?” I shoved documents around the desk, knowing she wouldn’t take the hint. “Froze to death. This is the fourth one. They find them in the parks, frozen.” “It has been cold,” I agreed. “You really haven’t been reading the papers.” Her eyes went on high-beam. “They’re wet, that’s why they freeze.” She sounded mad at me. Line forms on the right, behind my creditors. “Must be the tule fog?” I’d never been sure what tule fog was. I didn’t know if it required actual tules. “You have been in your own little world lately. They’ve all been passed out drunk. Someone pours water on them while they lie there. It’s been so cold they end up frozen to death.” … SNOW JOB First published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Jan/Feb 2019. Nominated for the 2020 Thriller Award for Best Short Story. She'd literally gone as far as she could. The undercarriage of her car was wedged on a tall ridge of ice between tire tracks. She was blocking the single plowed lane of the uncreatively named Main Street. She cut the engine. In the moment before the windshield went opaque with frost, she watched snow flurries blow sideways and upward in a manic swirl. The interior temperature plunged, the motor smell of her heater replaced by the fake floral of car wash carpet cleaner. Then the cold snuffed all scents, the air carrying nothing but chill. She grabbed her overnight bag and pushed the door open, feeling it slam into curbside snowpack. When she stepped out, her ankle boots crunched through its glassy surface, filling with powder. Before she could draw her first breath, her cheeks felt grated and her shoulders tensed into painful knots. This wasn't just a different microclimate from the city's—or even from the foothills below—it was a different planet. It was a distant frozen moon. It wasn't long past dinnertime, but nothing on the short street looked open. Not that there was much here: a weathered hardware store, a tiny market, a junk shop. The café that was her destination still had its lights on, though. Ava, wary of the uncleared sidewalk, turned back to her car and pulled a flashlight from the glove box. She was already late. She'd never driven in snow before. If she'd known how grueling it would be, she'd have phoned Aaron from one of the charming little towns below the snowline. She'd have pleaded with him to turn around and meet her someplace closer to home. But by then, she'd lost cell service. … THE CHILDREN First published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Sept/Oct 2011. Ella awakened face-down on the concrete. She spat out grit that swirled in the night wind, then rolled painfully to her side. The Kingstons' windows were dark but the glare of arc lights on their jack frost hurt her eyes. She dropped her gaze to an iron fence like a line of spears from the Corinthian porch to the next rowhouse. She struggled to free her arm from the sheet wrapped around her, but the effort made her lungs boil with coughs. Earlier, she'd come to with her nose mashed and her mouth covered, struggling to breathe through the filthy linen. She remembered twisting and slithering toward the gate, frantic to expose her face. Now, if she could pull herself through and tumble down the steps to the basement level service entrance, the wagon wouldn't see her when it passed. It wouldn't matter if she blacked out again, the drivers wouldn't mistake her stupor for death. They wouldn't toss her onto a pile of corpses stacked like cordwood. Maybe she could hang on till Cook came out for the milk. None of the servants knew that Charles, Cook's bad-tempered husband, had dragged Ella to the curb like garbage. He'd waited till long past midnight, and if he'd wakened Cook afterward, it would have been to take his vulgar pleasure, not to tell her what he'd done. Charles had been glad to get rid of Ella, she knew that. When the Kingstons brought home baby Annie, they'd wanted the house kept warmer at night. Charles always slept through extra stokings of the furnace, so Mr. Kingston forced him out of his wife's warm bed and onto a cot in the basement. To keep him from sneaking back to the attic room and passing out there, Mrs. Kingston sent Ella, till then on a feather mattress in the nursery, to take Charles' place, "problem solved." As if the Kingstons knew anything about problems. … CHAMPAWAT (a novella) First published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Sept/Oct 2012. Placed third in the vote for the 2012 Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine Readers Award. Part One Ella jerked awake. Her forehead, pressed against the train window, was cold with sweat. For two days, she'd been having the same nightmare. She was lying on the snow-dusted sidewalk, looking up at the Kingstons' windows. She kept trying to shout to them, to defy them with her survival. They were sure she'd finish dying before the wagon came. Why sit listening for the clatter of horseshoes? Even on their street of fine rowhouses, it might be dawn before the sheet-wrapped bodies were collected. The wagons filled faster every night, more and more of them rattling out of Washington to mass graves in Virginia. There were no coffins left and no plots in the cemeteries. Funerals, like all public gatherings, were banned by order of the mayor. They'd furled Ella into bed linens from the mending pile, hadn't they? She was only a servant, after all. For six hundred miles, Ella tried to stop reliving that night. She tried to focus on the scenery—forest and flatland glittering under frost, Pittsburgh, Akron, Cleveland spiked with girders of new buildings. But on every platform of every train station, some paper boy, cotton mask over his nose and mouth, waved the latest edition. Two hundred newly dead in one city, a thousand in the next, then four thousand, five thousand. The Philadelphia Inquirer screamed 50,000 Sick of Spanish Flu, 12,000 Perish. Now the train was pulling into Chicago, where Ella would transfer to another terminal. People around her were getting up and gathering their things. But she had only what she wore, a travelling suit and coat from Mrs. Kingston's tallboy, and the contents of her pockets. So she stayed in her seat, watching the station's bricks and arches come into view. She noticed three men standing on the frozen mud beside the tracks. They were a few steps from a platform that eventually disappeared into the terminal tunnel. They were well-dressed and hatless, puffs of breath visible as they talked. When her window passed closer to them, she felt a shiver of paranoia. They stood with chests out and heads high, every gesture self-pleased and full of swagger. In her experience, when men looked like they owned the whole world, they had badges and guns to justify it. Were these law men? She twisted in her seat, looking for—and seeing, she thought—the bulge of shoulder holsters under their jackets. Was railroad security preparing to come aboard? They'd been rousting draft-dodgers and Reds since the war began. And Ella had no papers. The Kingstons had burned her things in case sickness clung to them. … THE RIVER MOUTH First published in The Mysterious West, ed. Tony Hillerman,1994. Reprinted in A Moment on the Edge, ed. Elizabeth George, 2004. To reach the mouth of the Klamath River, you head west off 101 just south of the Oregon border. You hike through an old Yurok meeting ground, an overgrown glade with signs asking you to respect native spirits and stay out of the cooking pits and the split-log amphitheater. The trail ends at a sand cliff. From there you can watch the Klamath rage into the sea, battering the tide. Waves break in every direction, foam blowing off like rising ghosts. Sea lions by the dozens bob in the swells, feeding on eels flushed out of the river. My boyfriend and I made our way down to the wet clay beach. The sky was every shade of gray, and the Pacific looked like mercury. We were alone except for five Yurok in rubber boots and checkered flannel, fishing in the surf. We watched them flick stiff whips of sharpened wire mounted on pick handles. When the tips lashed out of the waves, they had eels impaled on them. With a rodeo windup, they flipped the speared fish over their shoulders into pockets they’d dug in the sand. We passed shallow pits seething with creatures that looked like short, mean-faced snakes. We continued for maybe a quarter mile beyond the river mouth. We climbed some small, sharp rocks to get to a tall flat one midway between the shore and the cliff. From there we could see the fishermen but not have our conversation carry down to them. Our topic of the day (we go to the beach to hash things out) was if we wanted to get married. Because it was a big, intimidating topic, we’d driven almost four hundred miles to find the right beach. Patrick uncorked the champagne—we had two bottles; it was likely to be a long talk. I set out the canned salmon and crackers on paper plates on the old blue blanket. I kicked off my shoes so I could cross my legs. I watched Pat pour, wondering where we’d end up on the marriage thing. When he handed me the paper cup of bubbles, I tapped it against his. “To marriage or not.” “To I do or I don’t,” he agreed. … DESTROYING ANGEL First published in Sisters in Crime 2, ed. Marilyn Wallace,1990. I was squatting a few feet from a live oak tree, poison oak all around me (an occupational hazard for mycologists). I brushed wet leaves off a small mound and found two young mushrooms. I carefully dug around one of them with my trowel, coaxing it out of the ground. I held it up and looked at it. It was a perfect woodland agaricus. The cap was firm, snow white with a hint of yellow. The gills under the cap were still white, chocolate-colored spores hadn’t yet tinged them. A ring of tissue, an annulus, circled the stipe like a floppy collar. A few strands of mycelia, the underground plant of which the mushroom is the fruit, hung from the base. I pinched the mycelia off and smelled the gills. The woodland agaricus smells like it tastes, like a cross between a mushroom, an apple, and a stalk of fennel. I brushed leaves off the other mushroom and dug it out of the ground. It resembled the first mushroom. It had a white cap, white gills, an annulus. But a fleshy volva covered the bottom third of the stipe like a small paper bag. It was all that remained of a fungal “egg” from which stipe and cap had burst; characteristic of Amanitas, not Agaricus. The volva was the reason I’d dug so carefully around the base of the mushroom. I had to be sure I’d dug the whole thing out. If I’d left the volva in the ground, the mushroom would have been virtually indistinguishable from the woodland agaricus. The mushroom was beautiful, pristine, stately, reputedly delicious (though you wouldn’t live to eat it a second time). But it was a deadly Amanita, a destroying angel, and I left it on the carpet of duff. … DO NOT RESUSCITATE First published in Crimes of the Heart, ed. Carolyn G. Hart,1995. She awakened with a prickle of dread like sharp-nailed fingers up her side. Then she closed her eyes again, closed them tight. One of her inner voices, sweet and coaxing, usually reserved for Hank, her husband of five years, chastised: Oh honey, don’t squish your face up. If Hank’s watching, he’s going to think you look like one of those dolls with dried apples for heads. Not that Hank would think any such thing. But she always made sure he couldn’t think anything crueler than she’d already thought herself: that way, she was dejinxed, protected. No matter that she didn’t need protection. She’d married Hank, seventy-three to her fifty-one, because he was absolutely devoted and uncritical of her, a big leathery old cowboy with a quick smile and a generous nature and, until his hard stroke three years ago, had a wonderful body for a man his age. Even with the stroke, his good conditioning and can-do attitude had brought him most of the way back. It had been a hellish few years, but except for kind of a pinched look on the left side of his face and some stiltedness in his walk, he was still her lean mean ranching machine. Just thinking of him soothed her unattributed anxiety on this chill November morning. She reached a plump, languid arm across the bed, feeling for Hank. Nothing. She fanned the arm as if making a snow angel. How odd: the sheets were cold. Whyever would the sheets be cold? … DREAM LAWYER First published in Diagnosis: Dead, ed. Jonathan Kellerman, 1999. Reprinted in The World's Finest Mystery and Crime Stories, ed. Ed Gorman, 2000; and First Cases, Volume 4, ed. Robert J. Randisi, 2002. “Picture this: a cabin in the woods, a hideaway, practically no furniture, just a table and a cot. Nobody for miles around, just me and her. I’m trying to keep her from collapsing, she’s crying so hard. Her tin god’s up and turned on her. “She’s got a gun there on the table, and I’m not sure what she’s thinking of doing with it. Maybe kill herself. So I’m keeping myself between her and it. I’m up real close to her. Even crying doesn’t make her ugly, her skin’s so fresh. Tell the truth, I’m trying not to get excited. Her shirt’s as thin as dragonfly wings, she’s all dressed up expecting him. She should be hiding from him, but all day she’s been expecting him. She’s been dreading him but hoping he’ll come, hoping he’s got some explanation she hasn’t thought of. Except she knows he couldn’t possibly explain it away. That’s why she’s tearing herself up crying. “She’s so beautiful with the light from the window on her hair. But she’s talking crazy—what she’s going to do now, how she’s going to tell everybody. Forgetting the hold he has on her, on all of us, how protected he is and how cool. “And then... in he comes. She shuts up right away, surprised and terrified. I can tell by how stiff she gets, she’s hardly even breathing. She’s too freaked out to say any more. That’s when I notice him there. But he’s not paying attention to me. He’s looking her over—her crying, the dress-up clothes she has on—and you can see he’s making something out of it. “She looks around like she’s going to try to run. Big mistake. He goes cold as a reptile. I’ve seen it happen to him before. And then he picks up the gun and shoots her right in the face. Just as cold as a snake. … PERFORMANCE CRIME First published in Women on the Case, ed. Sara Paretsky, 1996. I was about as stressed out as I could be. In addition to my work year starting at the university, I was trying to help get the Moonjuice Performance Gallery’s new show together. After last year’s fiasco, Moonjuice needed something accessible. And that would never happen unless someone displayed some sense, however tame that might seem to the artists. But the artists weren’t the main problem, the main problem was Moonjuice’s board of directors. The “conservative” members were two wannabe-radical university professors. The middle-of-the-roaders were a desktop publisher and an aspiring blues guitarist. On the avant-garde extreme was self- proclaimed bad girl and dabbling artist Georgia Stepp. I, an untenured associate professor, was so far to the right of other board members it was laughable. I was a fiscally responsible Democrat, which practically opened me to charges of fascism. I was trying to make my point about being sensible to Georgia. “We have to be careful after last year,” I insisted. “Last year was fun.” Georgia opened her long arms for emphasis. She wore a satin camisole, emphasizing a fashionable bit of muscle. Her nails were long and black. Her blond hair was cut short and dyed black this year. “We freaked out all the prisses.” She meant “prissy” board members who’d resigned in protest, convincing our sponsors to defund us and our program advertisers to boycott us. These were liberal restaurateurs and bookshop owners, hardly Republicans. “We have less than a quarter of last year’s budget because of that show. We’ve got artists working for free”—that got her—“and feminist university students volunteering elsewhere.” “Art can’t follow money like a dog in heat.” … EASY GO First published in Deadly Allies, ed. Robert J. Randisi & Marilyn Wallace, 1992. I kept my eyes on the sidewalk. River patterns of sticky urine congealed in the morning sun, catching pigeon feathers. Around me old men scratched and coughed and slid up walls they’d hugged for shelter in the night. Now and then, a briefcase darted by, a pair of shined shoes hurried toward City Hall, toward the Federal Building, toward the State Court of Appeal. I kept my eyes lowered. I knew too many lawyers in San Francisco, and they knew too much about me. The offices of the State Bar of California are just a few blocks from the heart of San Francisco’s Tenderloin. And the Tenderloin does have a heart: for the thousands of teenage prostitutes of both sexes, for the rummies and runaways and addicts at peep shows, there is at least a soup kitchen, at least a church with gaudily uplifting angels. But try to find the State Bar’s heart. It doesn’t have one, just a ledger. I climbed the steps. I should have been glad to climb them. I’d waited three years to do it. Three years plus one day since they’d cut off my buttons and epaulets. Three years of paying an “inactive status” fee (and galling it had been, believe me). Now, for an additional four hundred and thirty dollars and proof I’d retaken the professional responsibility exam, I would once again receive the wallet-sized card. Frances Valentine, it would read, Active Member, State Bar of California. After my disciplinary proceeding, a tragic-faced girl stopped me in the hall to say the State Bar was hiring. "You don’t need anything but a law degree to work here." It didn’t matter that my license had been suspended. I’d bitten my lip to refrain from telling her I’d rather empty bedpans. She didn’t deserve the splash of acid that had grown to replace pleasantries in my conversational style. … IF IT CAN’T BE TRUE First published in Irreconcilable Differences, ed. Lia Matera,1999. She regained consciousness seconds before the helicopter crashed. Gauges and instruments hurtled from one side of the claustrophobically small space to the other. Someone in the front was shrieking a panicked tone poem. Paraphernalia—stethoscopes, medicine bottles, clamps—hit her with the force of pinballs in a machine gone mad. An oxygen mask over her nose and mouth offered little protection. She surfed a wave of dread, realizing this had happened to her before. She prayed it was just a bad dream this time. When next she opened her eyes, she was still inside the helicopter but it was no longer in motion. A sheet of crushed laminated glass, glaring like glitter on glue, dazzled her. She was on her side, tipped toward the cockpit, the gurney wedged and buckled. A woman—a flight nurse?— was trapped under the gurney, her uniform soaked with blood. The nurse looked dead, red and wet like supermarket meat. She supposed her own survival was a testament to good packaging and the tensile strength of the gurney. The plastic mask cut into her face, still feeding her oxygen. Despite the fact that the gurney had twisted, the wristbands held. She jerked at them. Last time this happened, she’d been seat-belted like a passenger, not strapped down like an animal. … COUNSEL FOR THE DEFENSE First published in Sisters in Crime, ed. Marilyn Wallace, 1989. “I’m your lawyer,” I reminded him, in much the same tone I’d used in the not so distant past to say, I'm your wife. Jack Krauder glowered at the acrylic partition separating us from a yawning jailer. “Howard Frost is my lawyer.” “And Howard Frost is my associate—my junior associate. You hired a law firm, Jack, not a person.” “I asked for Howard.” “He’s in court. I'm not.” And I'm a better lawyer, anyway. “Through the miracle of modern science”—I fiddled with a small tape recorder—“Howie can hear everything you tell me. If you make up your mind to tell me what happened.” “You don’t believe me.” His voice was carefully uninflected, a contractor’s trick he’d perfected on angry homeowners and stubborn zoning boards. “You lived with Mary Sutter for how long? Six months?” Seven months and nine days, to be exact. “You must know something. More than what’s in here.” I tapped the police report. “Remember how I used to complain about my clients lying by omission? Ransilov, remember him? Leaving me open to that surprise about… Jack?” I slid a sympathetic hand across the gouged metal table that separated us. “Don’t booby-trap your own defense.” Jack released the arm of his chair, dropping his hand onto the table like a piece of meat. He frowned at his chafed red knuckles, apparently unable to will the hand to touch mine. Two years of connubial hell will do that to a relationship. … |